As part of our ongoing project examining how the use of EdTech in schools can ameliorate or reinforce social and educational inequalities, we secured additional funding to speak directly with EdTech companies. Through this process we have been able to learn more about the motivations, perspectives, and experiences of EdTech developers, including how they approach designing for equity and what kinds of collaboration and evidence they would like from researchers. These conversations have been invaluable as we begin creating Open Educational Resources aimed at supporting the creation of more equity-focused EdTech.

Isabel Goddard and Liam Bekirsky

The EdTech sector represents a substantial and rapidly expanding global market. In 2020, it was estimated to be worth $89.49 billion USD and has been projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 19.9% from 2021 to 2028 (International Trade Administration, n.d.) In practical terms, this means that EdTech has transformed from being a relatively small and specialised market into a global one that attracts significant investment. Although 2024 marked a notable turning point, with growth in the sector slowing after several years of rapid pandemic-driven expansion, the EdTech market remains vast (HolonIQ, 2025). The sector is likely to continue growing with the significant market excitement around AI and shifting investor focus to AI-driven technologies.

It is estimated that UK schools spend approximately £900 million per year on educational technologies, making it the largest EdTech sector in Europe (Department for Business and Trade, 2025). Indeed, our ethnographic research has revealed the extensive reach of EdTech across the education system, though the types of technologies and the ways they are implemented vary considerably. First-hand observations highlight a complex landscape with EdTech used for a wide range of activities and purposes including, for example, ‘personalised’ learning technologies, behaviour management, and the creation of educational resources – reflecting the sector’s breadth and diversity.

The commercial landscape of EdTech is complex, with products developed by a range of actors, from Big Tech such as Google and Microsoft to EdTech startups, and independent and acquired EdTech companies. Each type of provider operates with different motivations and approaches and plays a different role in this space. In this work, we focused particularly on smaller and independent EdTech companies as we believe this is where change toward more equity focused EdTech in the commercial sector is more likely to occur and have the greatest impact on the UK market.

Before engaging with EdTech developers, we conducted a market mapping exercise to better understand the landscape of these independent and often smaller companies operating within the UK. Using data from the financial data and research platform, PitchBook, we identified over 1,000 active EdTech companies in the UK. After excluding companies that did not build products for primary and secondary education, we coded the final sample of 350 companies by category of purpose the products were designed to achieve. The coding schedule was developed from our ethnographic work in schools and commercial categorizations (e.g. Department for Education, 2022).

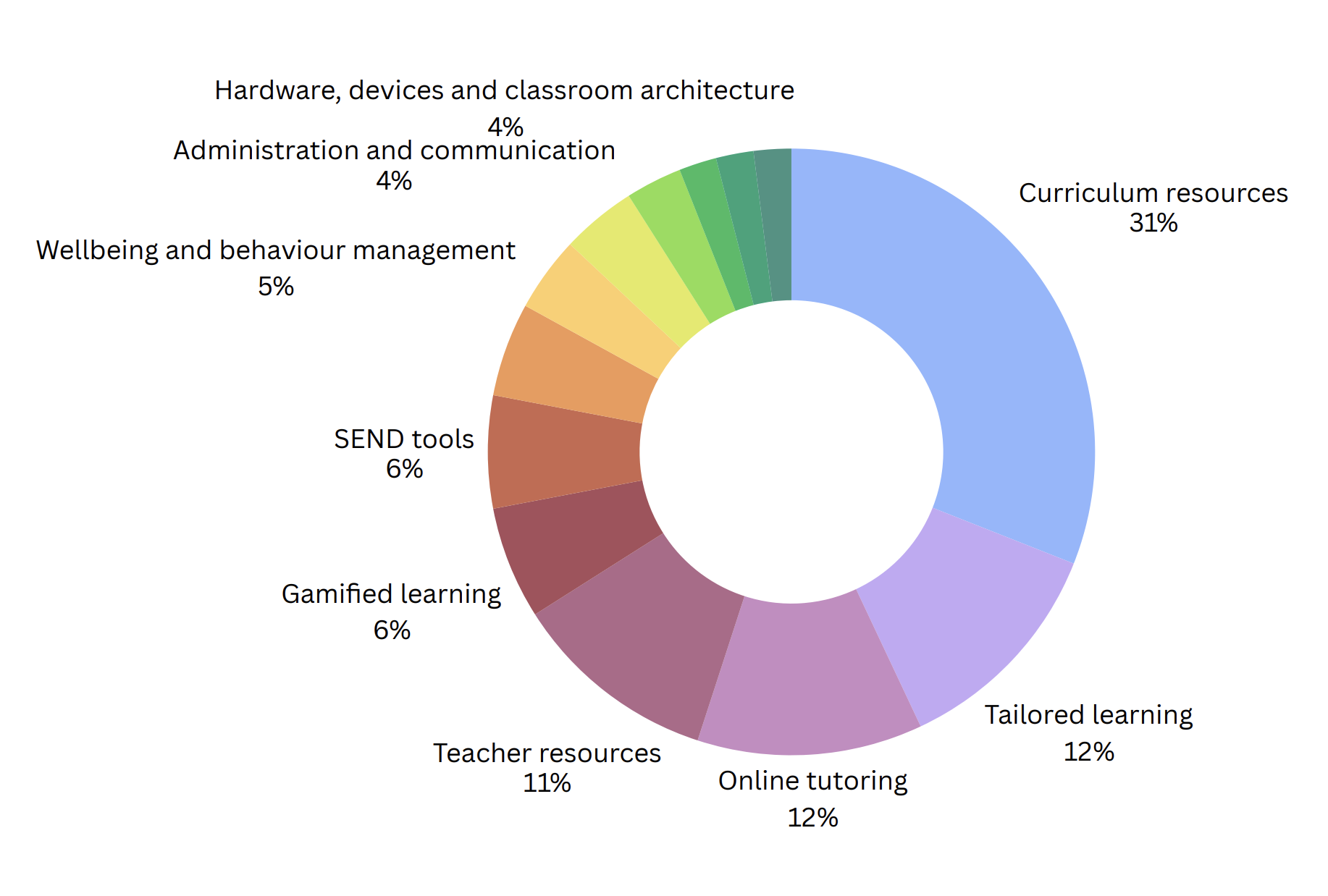

The data provided an overview of the composition of the market and the types of companies in the sector. Among independently owned firms, around a third (31%) provide curriculum resources for students, while smaller proportions focus on tailored or “personalised” learning (12%), online tutoring (12%), or teacher resources (11%) (figure 1). Most of these independent companies are relatively small, employing fewer than 50 people.

Fig. 1 Distribution of activities among independent EdTech providers

Acquired companies show a slightly different profile. While curriculum resources remain important (22%), administration and communication tools are nearly as prevalent (21%), reflecting the types of products that typically attract larger tech firms during acquisitions. While a large number of small, specialised companies provide a diverse range of educational products and services, certain types of technologies – particularly those supporting curriculum and administration – tend to feature significantly in the landscape.

This exercise provided a starting point for understanding who these EdTech companies are, the interests that drive them, and the types of products they develop. Importantly, it helped us identify potential EdTech companies to speak with as part of the second phase, ultimately advancing our aim of translating rich ethnographic data into resources that EdTech companies can use to support the design of more effective and fairer technologies for education.

References:

Department for Business and Trade. (N.d.). EdTech. Available at: https://www.business.gov.uk/invest-in-uk/investment/sectors/edtech/.

Department for Education. (2022). The education technology market in England. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/636e7717e90e07186280f7cf/Edtech_market_in_England_Nov_2022.pdf.

HolonIQ. (2025). EdTech VC reached ∼$2.4B for 2024, representing the lowest level of investment in a decade. Available at: https://www.holoniq.com/notes/edtech-vc-reached-2-4b-for-2024-representing-the-lowest-level-of-investment-in-a-decade.

International Trade Administration. (N.d.). Educational Technology. Department of Commerce ITA. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/education-technology.

Funding acknowledgement:

This research was supported by the University of Oxford’s Social Sciences Division and funded by the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF).

Photo by freepik.com.